Reading time: 10 minutes

Housing Policy is Environmental Policy.

This Earth Day, as we shelter at home, let’s take a moment to consider one of the most important environmental choices we make as a society — our housing policy. The way that we use land to house ourselves has tremendous potential to preserve wilderness, cut air pollution, and bend the curve on climate change.

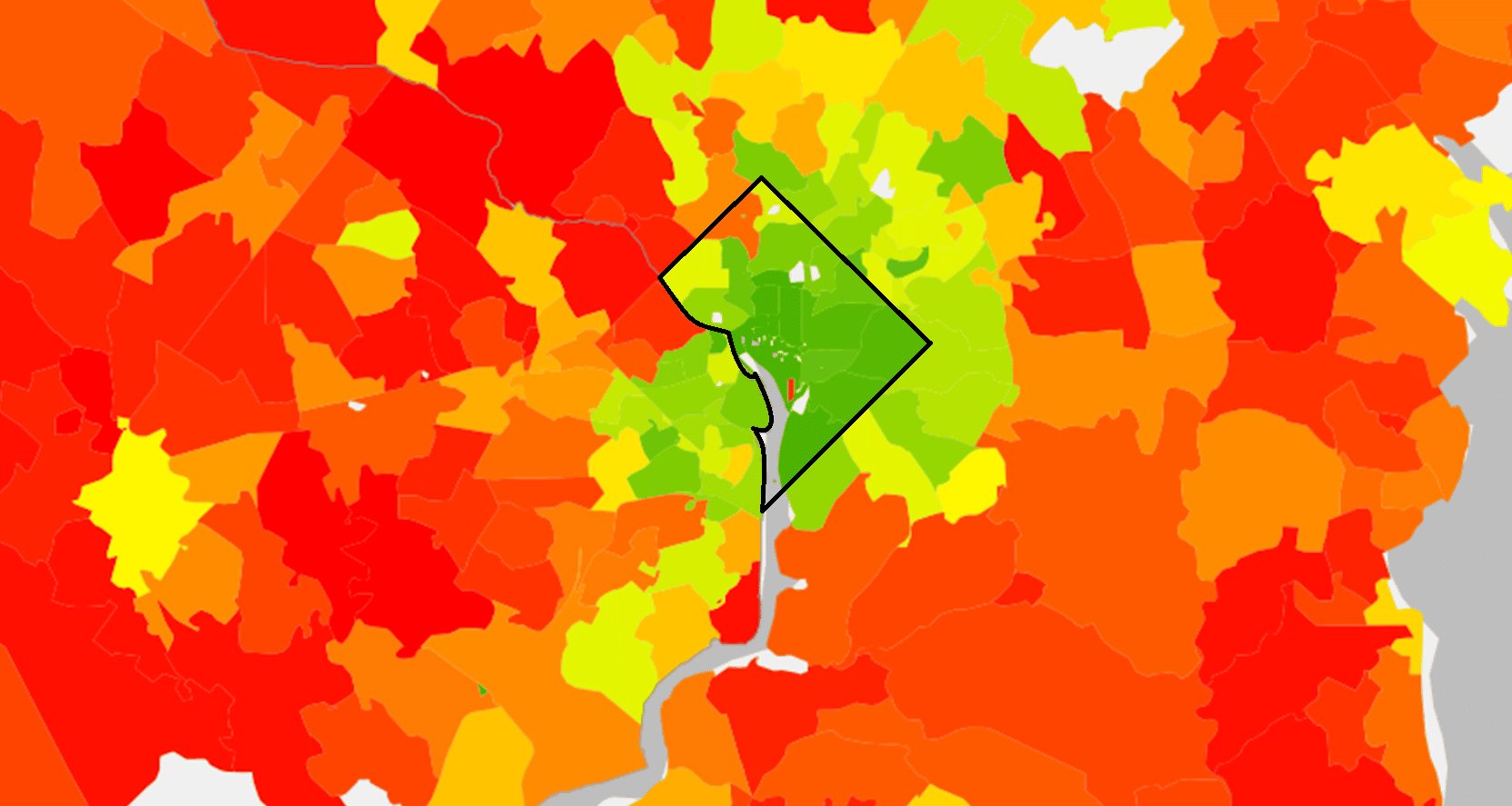

The map below, put together by UC Berkeley researchers as part of the CoolClimate Network, illustrates the close relationship between land use and the greenhouse gas pollution that causes climate change. It uses a color scale of green to red to visualize the average household climate emissions in the Washington, DC area. In urban DC, emissions range from roughly 20-40 tons of CO2-equivalent per household each year. But in the Maryland and Virginia suburbs, emissions are generally 60-90 tons/household — double or triple that of a typical DC household.

his pattern holds throughout the United States. In almost every major metropolitan area, high emissions in suburbs more than outweigh the lower emissions in urban cores. With a need to slash overall emissions to avert the worst of climate change — by 50% in a decade and 90% or more by midcentury — we cannot succeed without a fundamental shift in housing and land use policies, both in urban cores and in suburbia.

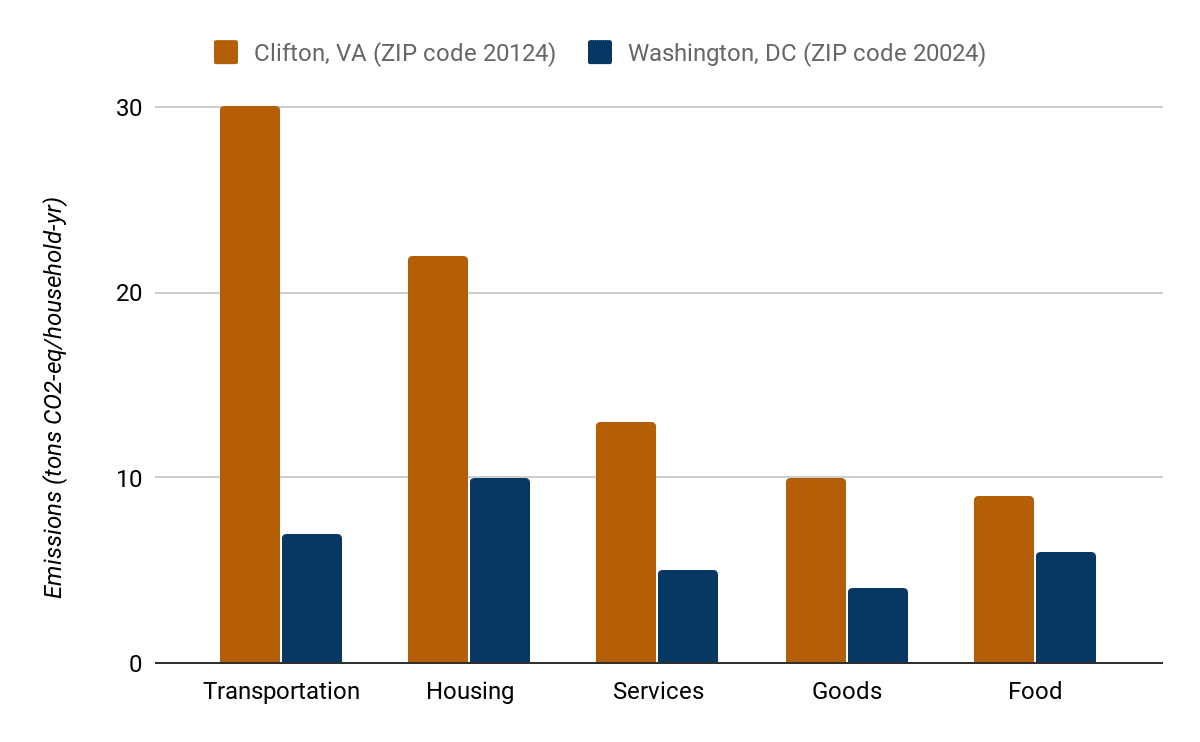

The accompanying UC Berkeley study provides three main explanations for high suburban emissions: higher incomes, higher transportation emissions, and higher housing emissions, as you can see in the chart below comparing emissions in suburban Clifton, VA and in a typical Washington, DC neighborhood.

Annual Emissions per Household

The stark differences in transportation and housing emissions are simple to explain: they have everything to do with housing policy. As Up for Growth put it in one of its Insights Reports, housing is the environmental issue of our time. America is dominated by a suburban environment with large, single-family homes, where long distances to work and amenities lead to car dependence. This locks most of America into a lifestyle of high carbon emissions. This pattern can be found in both red states and blue states, large states and small states, and especially in car-centric California, where we are based.

Isn’t California leading the way on the environment?

California is both a national leader in fighting climate change (in 2018 more than half the state’s electricity came from carbon-free sources) and a poster child for environmentally destructive land use policy, epitomized by sprawling suburbs. Yet state leaders have recently started to recognize the link between housing policy and climate change, and have taken small steps towards addressing the problem.

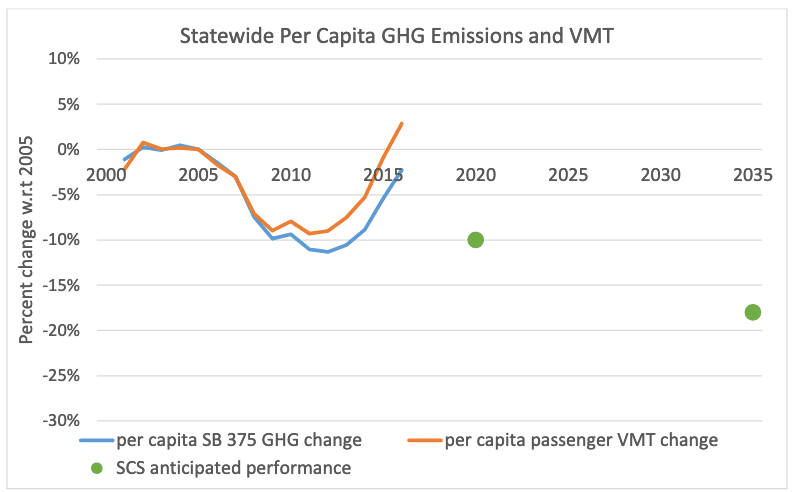

In 2008, California passed the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act (SB 375) to help reduce driving and sprawl. But Californians are driving more since the bill’s passage: after a dip during the Great Recession, vehicle miles traveled per person increased by 14% for passenger cars and trucks over the 5 years ending in 2017. (California Air Resources Board and Department of Finance.) As transportation accounts for more than half the state’s climate pollution (when counting petroleum refining and extraction), this trend is overshadowing California’s success in cleaning up electricity, and it is the biggest roadblock towards achieving the state’s 2030 emissions goal — which the state will not meet until 2050 if progress does not accelerate.

Per capita vehicle emissions and miles travelled, heading in the wrong direction. The green dots represent the original policy goals. Reproduced from the California Air Resources Board.

Why are Californians driving more, despite state policy goals? The simplest reason is that our transportation and land use decisions are not aligned with our climate goals. Like most of the US, local governments have a near-monopoly on the decisions of what and where to build, effectively zoning out the mixed-use, multifamily development that lessens car-dependence. Even where such housing is legal, it is often smothered in endless review processes easily hijacked by a small minority of self-interested neighbors. Meanwhile, our transportation spending and the rules of our streets still largely assume that private cars are the only form of transportation that counts: this makes cars the cheapest and most convenient option for many trips, effectively ensuring that alternatives never reach their full potential.

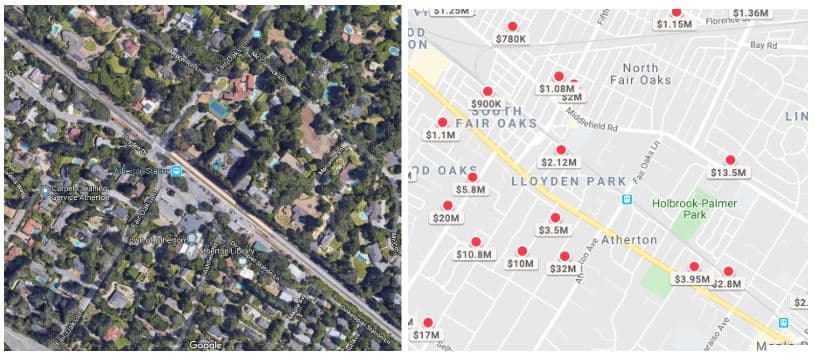

Single-family zoning in cities and nearby suburbs, long used across the US as a tool for imposing racial segregation (see Timeline of 100 Years of Racist Housing Policy that Created a Separate and Unequal America.) also leads to more driving. This is because it limits these neighborhoods — as well as the high-quality transit and other amenities often found in them — to just a small number of residents. Any additional residents of the metropolitan area — generally those with lower incomes who cannot afford a single family home in a central location — are pushed into exurban areas, where they often endure long, polluting car-based commutes. In the San Francisco Bay Area, a growing number of “super commuters” drive more than 90 minutes each way to and from work.

Atherton Caltrain station, easily accessible only to a select few within walking distance (satellite image, left) and with the necessary financial means (home prices from Zillow, right).

Even worse, the exclusion of homes from our cities has pushed more people into the “wildland-urban interface,” where tracts of single-family homes meet grasslands and woodlands and risk being burned in wildfires. We cannot assume the unprecedented California wildfires of 2017-2019 and the Australia wildfires earlier this year are the “new normal”: in fact, things will only get worse if we don’t change course.

It’s time for bolder action.

In this time of great suffering caused by viral pandemic, it is clear we can no longer afford to be complacent with systemic risks to our civilization. In the past decade, we have made enormous progress in the electricity sector, and in recent years, a growing chorus of activists have called for banning or divesting from new fossil fuel projects, transitioning our electricity system to 100% renewable or carbon-free power, and eliminating the sources of toxic air pollution choking our most vulnerable communities. It is time for a similar refrain for housing policy reform from within and beyond the environmental movement.

Yes, we can build more efficient homes, and yes, we can switch to electric cars. But these efforts, while important, are not sufficiently transformative to address the urgency of the climate crisis. Governments must address the housing shortage and target future growth to benefit the environment and the economy. Housing policy should encourage multifamily infill development in both urban cores and in suburban commercial districts, especially near transit and job centers. This will bring about massive energy savings — a new multifamily home uses about half as much energy as a single family home in California (see figures ES-31 and ES-33 in the 2009 California Residential Appliance Saturation Study). Moreover, it would enable more Americans, especially lower-income families, to finally say goodbye to car dependency and super-commuting.

Research from Up for Growth underscores why focusing on urban-infill development and building housing near transit has tremendous environmental benefits. If California were to address its 3.4-million unit housing shortfall through this so-called “smart growth” approach, the new housing could result in 36% less carbon emissions, 77% less land development, and 35% fewer vehicle miles traveled than under current building patterns.

In the state legislature, Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez has proposed a bill that would help to accomplish this goal. Her bill, Assembly Bill 2345, would permit up to 50% more housing units in multifamily residential buildings, in return for setting aside a percentage of units that are affordable to renters with either low or moderate incomes. This density bonus program is based on a similar law in San Diego that helped double apartment construction.

Passing AB 2345 would help California take a meaningful step away from sprawl and car dependency. It would create more homes in walkable, mixed-use corridors with easy access to jobs and transit. It would help residents with low incomes — those who are likeliest to be pushed into super-commutes by high housing costs — to afford to live near jobs and opportunity. And all of this would reduce carbon emissions and assist in the fight against climate change.

This bill alone will not solve California’s environmental problems (no single bill can), but it offers a valuable opportunity to redefine housing and land use policy in a way that supports a healthier climate. California should pass it, and other states should take similar measures to encourage climate-friendly housing and living.

We can think of no better tribute to the spirit and goals of Earth Day than ensuring the policies that affect something important as where and how we live are also good for the environment.