What is Housing Underproduction?

Housing Underproduction occurs when communities fall short of meeting housing needs. Up for Growth calculates underproduction as the difference between total housing need and total housing availability.

For the first time in nearly a decade, housing availability increased in the top 25 major metropolitan areas. On its surface, this seems like positive news for owners and renters. Instead, it tells the story of a deepening crisis resulting from a century of exclusionary housing policy and set off nearly a decade ago by major demographic shifts, a historic economic recession, and chronic housing underproduction.

Drivers and Trends

Not since the beginning of suburbanization in the early 20th century have household formation patterns shifted as dramatically as they have since March 2020. Although the United States produced more housing units in 2020 than in 2019, it was insufficient to meet demand, and production was misaligned with quickly shifting preferences for where people wanted to live.

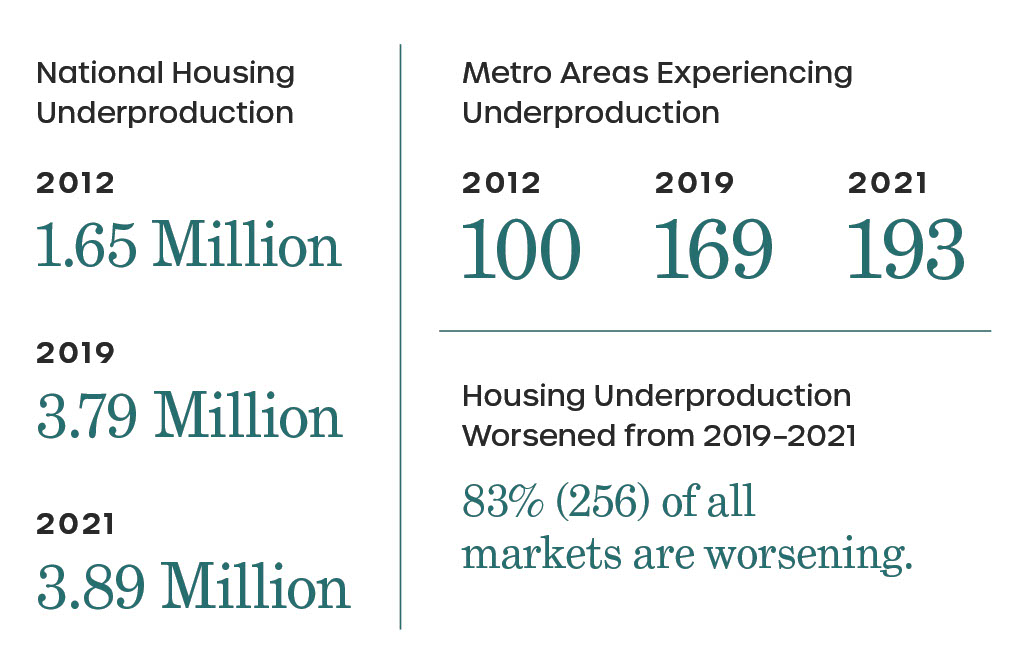

Housing Underproduction is Getting Worse

Nationally, underproduction increased by nearly 3% to 3.9 million missing homes.

It is Spreading Geographically

The number of counties across the U.S. experiencing underproduction increased 32%.

It is Shifting from Urban Areas to Suburbs and Small Towns

Driven by population loss, housing availability increased 0.3% in urban America. Housing underproduction increased by 4.5% in the suburbs, spurred by high levels of household formation. Due to a sudden and dramatic drop in unit delivery, housing underproduction increased by 47.8% in small towns.

A Brief History of Housing Underproduction

In the face of unprecedented housing demand, why is America building fewer homes than ever?

To answer this question, it is essential to understand how economic, social, and policy forces converged throughout history to shape housing supply and demand.

Housing Policy Milestone

Housing Market Milestone

U.S. Economic Milestone

1869

The first “Streetcar Suburb” develops outside of Chicago in Riverdale, IL.

1910

First race-based zoning ordinance in Baltimore, Maryland

1917

Buchanan v. Warley; Rules race-based zoning unconstitutional

1926

Euclid v. Amber upheld use-based zoning

1934

Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and Federal Housing Administration (FHA) are created

1942

U.S. Congress enacts Federal Rent Control

1945

Levittowns usher in urban sprawl

1950s

Urban Renewal and Blight Removal

1956

Federal-Aid Highway Act Passes

1960s

Birth of the Slow-Growth Movement

1962

U.S. Congress passes tax incentives to spur housing development

1968

Fair Housing Act passes

1969

National Environmental Policy Act Passes

1972

U.S. reaches peak housing production

1986

U. S. Congress removes 1962 tax incentives but creates the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC)

1992

Wall Street creates the securitized mortgage market

2003

26-year high in housing production

2009

Housing production falls below the long-term average and does not rebound

2015

Beginning of Return to the Suburbs

2020

Beginning of global COVID-19 pandemic

1820 - 1929

American Urbanization and an Era of Housing Abundance (1820 – 1929)

From the early 19th century through the 1920s, the American Industrial Revolution transformed the nation from an agrarian society into a majority urban one (Taeuber, 1941). Advances in transportation in the 1870s led to the growth of streetcar suburbs beyond the urban core (Hayden, 2004). These streetcar suburbs provided an alternative to overcrowded city centers, drawing long-standing residents and opening space for waves

of immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe seeking opportunities in American cities (Boehm & Corey, 2014).

By 1920, over half of the U.S. population lived in urban areas (Census History Staff, 2022). Fueled by economic opportunities, cities like Chicago and San Francisco became targets for migration (Schleicher, 2017). With the exception of a brief housing shortage and early experiments with rent control following World War I (Fogelson, 2013), limited regulation supported abundant housing construction. Rapidly growing cities were able to house throngs of newcomers, creating widespread economic opportunities and boosting the young nation’s economic productivity (Fischel, 2016).

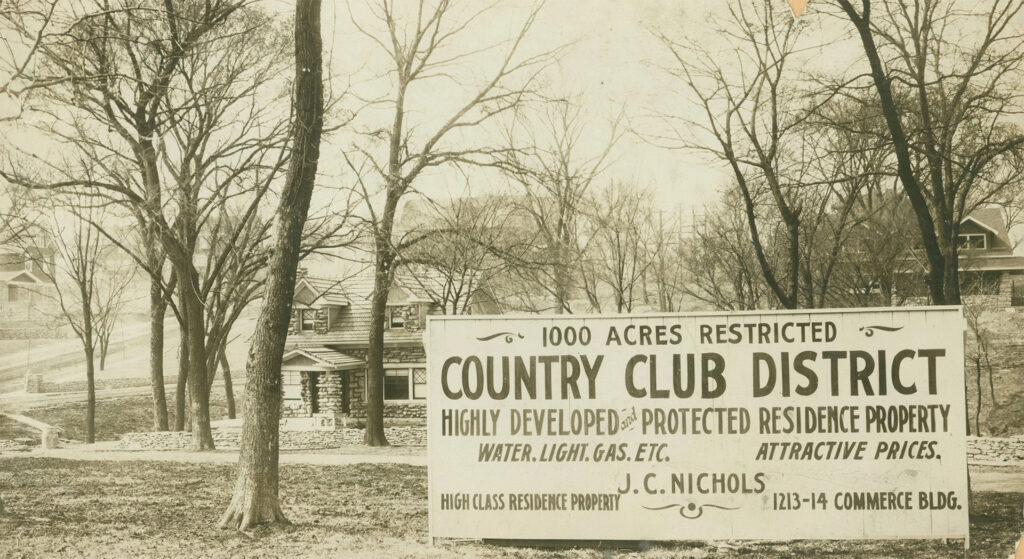

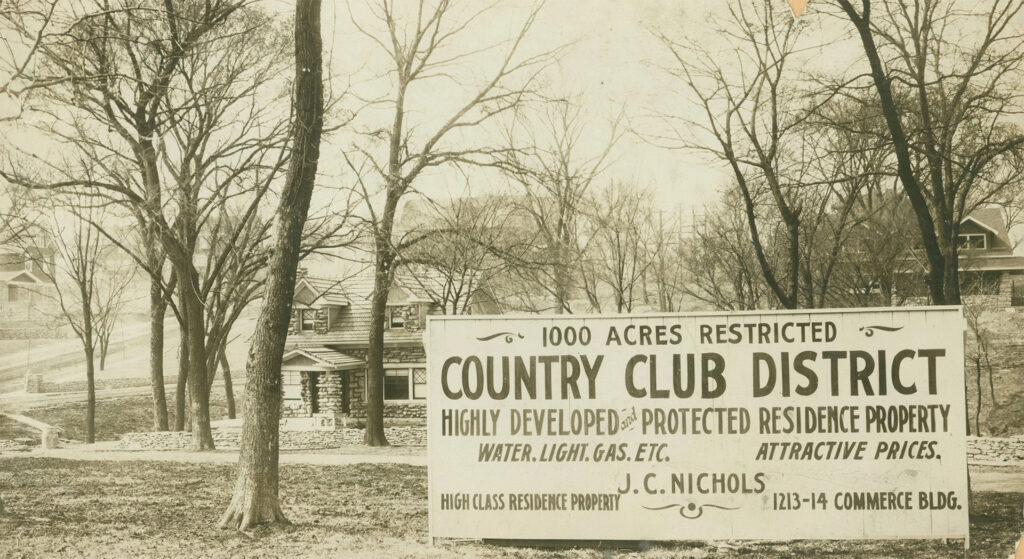

With so many Americans living in close proximity to one another, new challenges arose. Pollution, poor sanitation, and unsafe living conditions in downtown business districts were common (Riis, 1890). Social tensions also began to surface, in part a reflection of the global rise of nationalist and racist ideologies (Higham, 2002). Many white and upper-class individuals, uncomfortable with the increasing diversity and density of the city, sought refuge from these burgeoning urban centers. Around this time, the enactment of the first racial zoning ordinances (Pietila, 2011) signaled the beginning of what would eventually be called “white flight” (Shertzer & Walsh, 2018). Although race-based zoning ordinances were ruled unconstitutional, they were soon replaced with use- based zoning codes often deployed to similar effect.

1929 - 1948

The Great Depression and the First Period of Housing Underproduction (1929 – 1948)

On October 29, 1929, Black Tuesday ushered in the Great Depression. Its far-reaching impacts included a significant downturn in the housing market. By 1933, home values had fallen 35% (Davies, 1958), more than 250,000 people had lost their homes to foreclosure, renters fell behind and faced eviction (Fishback et al., 2013), and construction of residential property fell 95% (Glabb & Brown, 1967).

In response to the housing crisis, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal aimed to stabilize the market through key programs like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). While these agencies helped steady the housing market, they also institutionalized the practice of redlining, which led to the racial segregation of communities (Rothstein, 2017). The federal government also aggressively encouraged exclusionary zoning through a series of requirements and incentives (Toll, 1969). Just as the New Deal policies began to take effect, the nation’s focus pivoted to World War II. Most non- essential construction, including residential projects, was halted, and rent control was introduced through the Emergency Price Control Act of 1942, a measure to prevent price gouging during a period of constrained supply.

A Note on Rent Control

Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman noted in 1946 that World War II-era rent control carried significant social costs, including deterioration in the quality of rental housing and the disincentive to build new rental homes (Friedman & Stigler, 1946). Resulting disinvestment in inner city rental housing set the stage for urban renewal and blight removal in the 1950s.

From the 1930s onward, America settled into a prolonged period of housing underproduction (Newcomb & Kyle, 1947). Fueled by war-related job growth and then by the demobilization of 16 million troops and the subsequent baby boom, America’s urban population grew four times faster than it had during the previous decade (Boehm & Corey, 2015).

This population boom, coupled with slow residential constructionduring the economic downturn of the 1930s, caused housing tobecome both scarce and expensive. Housing vacancies in April 1940 stood at a little under 5%, plunging to a mere 1.4% by November 1945 (von Hoffman, 2012). By 1946, six million people were living with relatives due to housing scarcity (Palen, 1994).

1948 – 1990

Suburbanization and Slow Growth (1948 – 1990)

In anticipation of the end of World War II, the Urban Land Institute, an authoritative voice in land use and real estate, predicted an “almost limitless demand for new housing in post-war America” (1942). Propelled by a mix of federal and local policies, this prediction manifested in the form of suburban sprawl. Exclusionary zoning laws from the 1920s made building near existing urban centers difficult, and the Federal- Aid Highway Act of 1956 incentivized suburban growth through federally subsidized infrastructure.

Developers like William Levitt capitalized on this by mass-producing single- detached homes primarily in what had been rural areas. These ventures were facilitated by federal mortgage financing that came with conditions that perpetuated racial segregation by enforcing a whites-only requirement (Rothstein, 2017). Within a few years, thesenewsuburbandevelopmentsclosedthe housing gap but only benefited anexclusivelywhitedemographic(Palen,1994).

As these suburban communities matured, restrictive zoning policies gained traction, with California pioneering the slow-growth movement in the 1960s. This approach, which limited housing construction even as populations grew, was subsequently adopted by other cities across the U.S. (Morrow, 2013). The rise of the environmental protection movement in the 1960s and 70s offered NIMBY activists tools for opposing development (Frieden, 1979). Legislation like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), intended to protect natural resources, also empowered local resistance against housing projects, making new development more difficult.

1990 – 2008

Economic Expansion and Return to Cities (1990 – 2008)

As America entered the 1990s, the economy was in a state of unprecedented stability, often referred to as the Great Moderation (Hakkio, 2013). This economic calm was accompanied by significant societal and financial shifts. The 1970s and 1980s brought a sharp and steady decline in household size (Nelson, 2013), and by the 1990s, the popular appeal of city life was growing (Leinberger, 2009). The tech and finance sectors flourished, and a growing consumer preference for urban convenience, coupled with increasing awareness of the repercussions of suburbanization, prompted a significant return to city-life. Yet, renewed urban demand collided with housing constraints created by earlier downzoning efforts.

Amid this backdrop, remnants of the 1980s savings and loans crisis lingered. The U.S. Congress had created the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), which introduced innovative financial instruments to resolve the assets of failed savings and loans associations. One such tool was the commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS), wherein Wall Street and the RTC repackaged non-performing loans into securities for investors (Mandzy, 2017).

The CMBS market quickly exploded in prominence, providing an influx of credit and liquidity. By the early 2000s, the CMBS market overtook life companies as the second largest category of commercial real estate lending (Chandan, 2012). The growing market share of CMBS lenders offering very aggressive terms also led banks and life companies to loosen their underwriting standards and mortgage terms in order to remain competitive (Wilcox, 2012). Housing supply limitations, coupled with intense demand, drove up home prices. Loose lending standards and risky financial speculation created a housing bubble that would soon burst.

In 2008, the inevitable happened. Capital markets, straining to capture red-hot demand for housing, imploded, plunging the nation into the Great Recession (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2018). Financial instability and a return to tighter mortgage lending standards led many to continue to rent rather than buy (Fry & Brown, 2016), further straining urban rental markets. Housing production came to a standstill, and millennials—America’s largest living generation—became the first generation unable to buy a home at the age their parents did (Both, 2023).

2008 - Present

Second Period of Housing Underproduction (2008 – Present)

The repercussions of the Great Recession persist. Even fifteen years later, the U.S. has not matched pre-recession housing starts. Around 2015, many millennials started families. Household formation spiked, and driven by the pursuit of affordability and space, millennials looked to settle in suburbs and small towns.

A Note on Rent Control

In 2016, in response to skyrocketing rental prices, calls for rent control began to spread like wildfire. If today’s rent control measures pass, we could expect to see owners remove their properties from the rental market, disinvestment in existing rental properties, and a decrease in production of new housing.

National Takeaways

Housing Underproduction in the Suburbs

Between 2015 and 2019, housing underproduction in the suburbs increased by 16% annually, compared to 9% in urban centers. Nationally, the suburbs hold a disproportionate 48.7% (1.9M) of total housing underproduction. Despite a surge in suburban household formation, new home construction has not kept pace. For every 100 new suburban households formed in the reporting period, only 67 new homes were delivered, indicating a deep mismatch between the housing stock available and the demand for housing in fast-growing suburbs.

To create a more balanced housing market, American suburbs must build enough housing to cover their deficit and then more to keep up with growing demand. Yet, in most suburbs, NIMBYism is proving effective at preserving exclusionary zoning and burdensome regulatory restrictions. Keeping up with housing demand is nearly impossible.

Housing Underproduction in Small Towns

From 2020–2021, household formation in small towns across the U.S. spiked by 300,000, while at the same time, new housing construction dropped 13.2% from long-term trends. Affordability is one of the attractions of living in small towns, but lack of infrastructure and limited access to labor and supplies can add significant expense to new development. Furthermore, household wages in small-town markets tend to be too low to cover these added costs, and many new projects are deemed infeasible before they even begin.

Housing Underproduction in Rural America

Despite continuous population loss in rural communities, housing underproduction has quadrupled since 2013. Moreover, housing in rural communities is aging. Federal disinvestment and the challenges that come with building in rural areas combine to make the cost of new development too high to justify. Increasingly, it seems reinvestment in an aging housing stock and expanding infrastructure may be the best solutions to meeting housing needs. But federal investment is key to helping rural communities thrive.