Reading time: 6 minutes

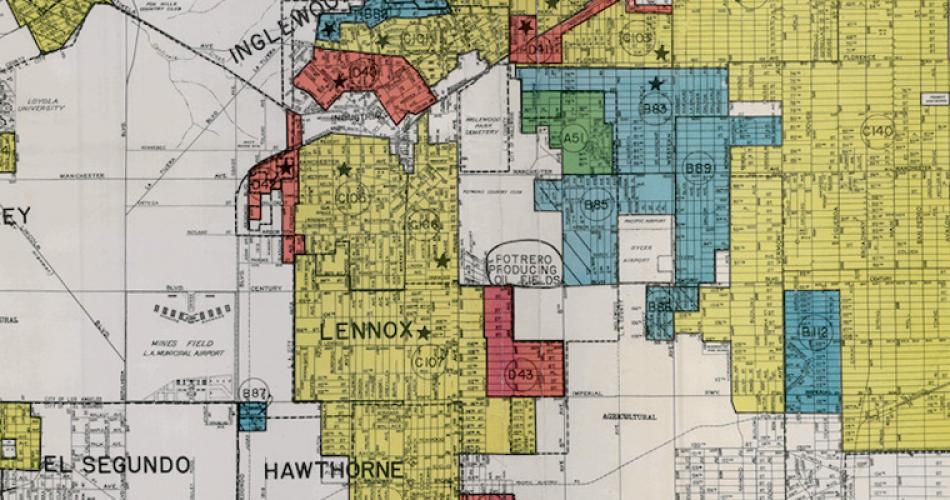

In the 1930s, the federal government created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), which produced Residential Security Maps (commonly known as redlining maps). The attitudes and language found in HOLC appraisal sheets and Residential Security Maps created by the HOLC were fundamentally racist in nature and, despite the earlier Supreme Court ruling, essentially relegated African Americans to the least-desirable and least-upwardly mobile parts of a city. In effect, these maps gave federal support to mid-century real-estate practices that would solidify residential segregation in America – the legacy of which lives on today.

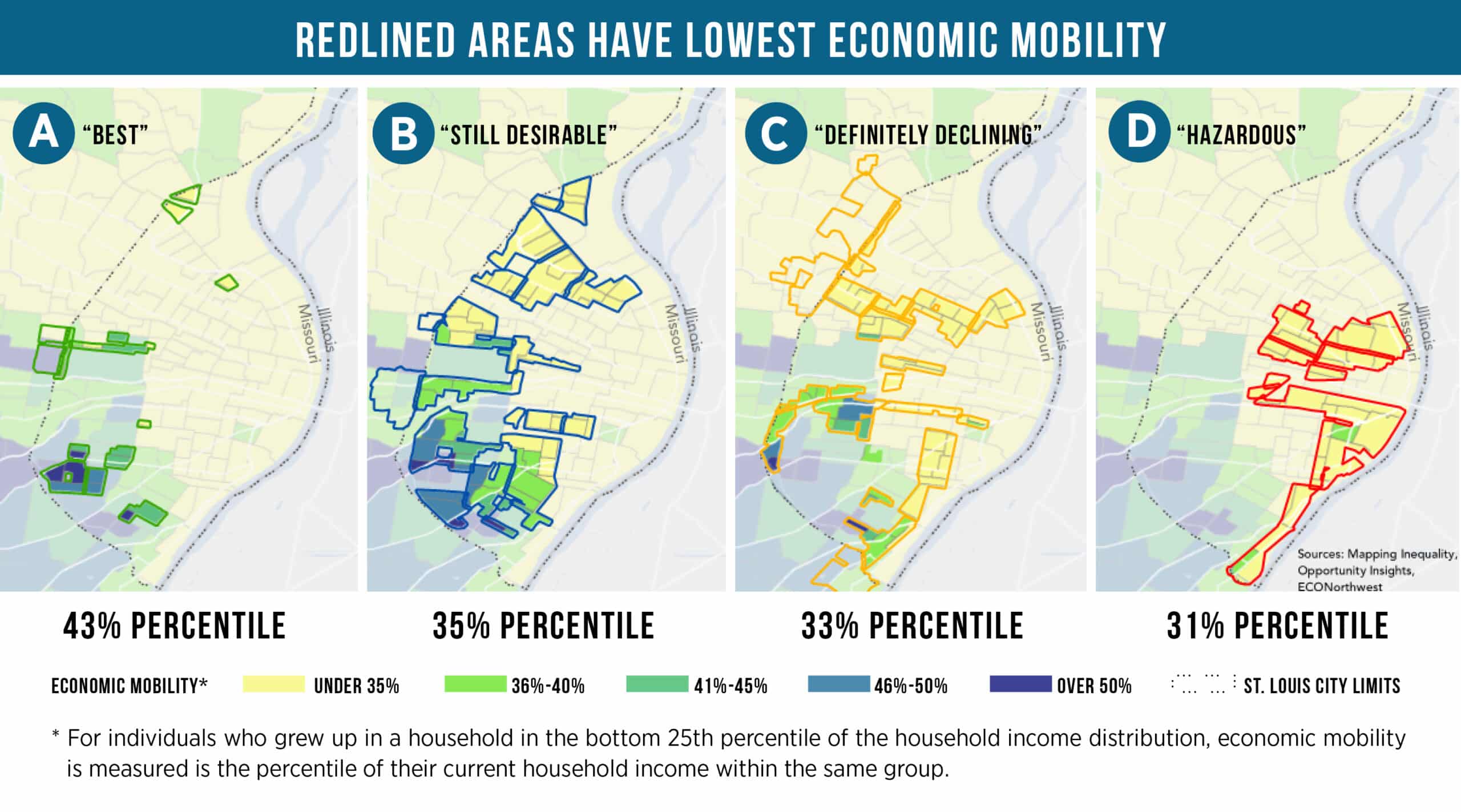

St. Louis is an example of how these maps still impact a city and its people in the 21st Century. Zoning was first created in St. Louis in 1918, a year after Buchanan v. Warley. Based on the HOLC Residential Security Maps, 15% of the City of St. Louis was coded as Grade A, or “Best,” and 38% of the City of St. Louis as Grade B, or “Still Desirable.” Even today, children within households that grow up in areas of St. Louis that are classified as Grade A or B have better economic mobility than children within households that grow up in areas of St. Louis that are classified as Grade C or D.

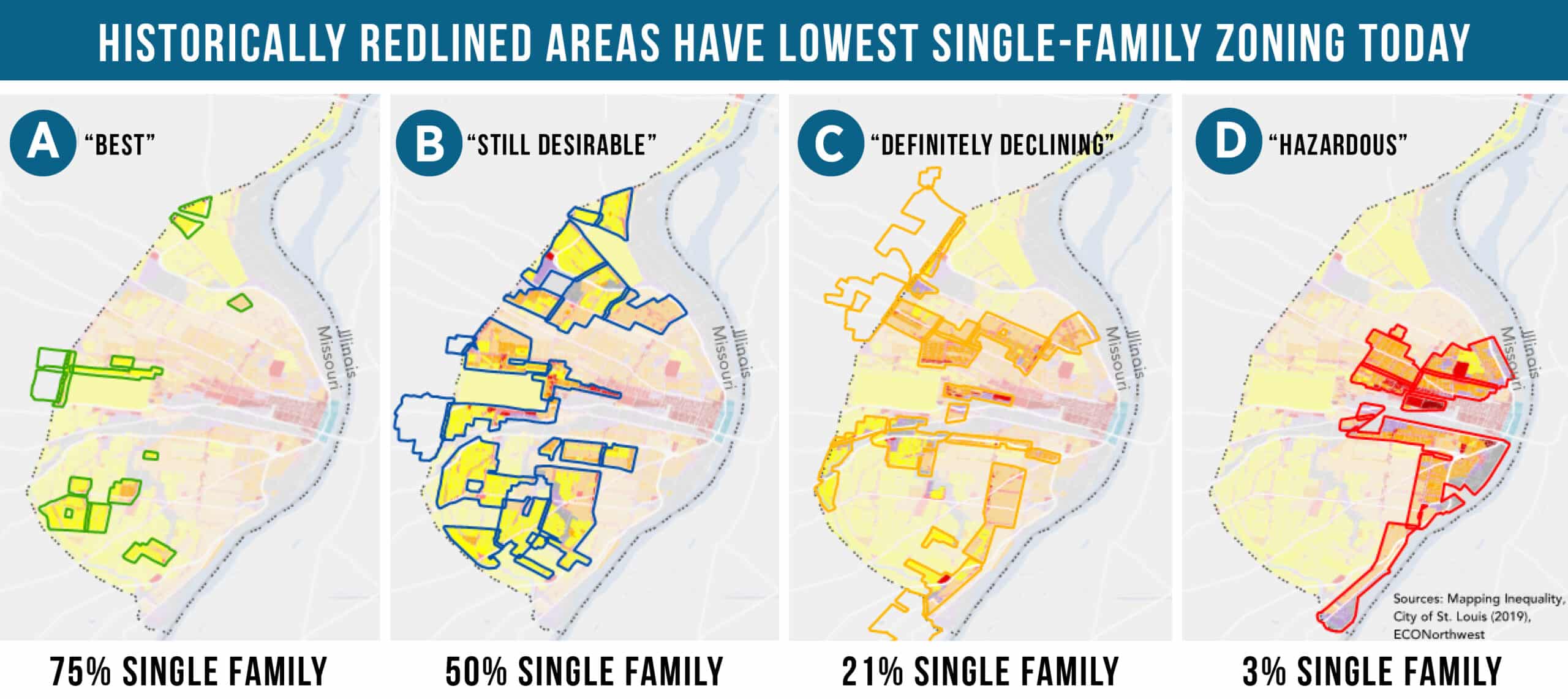

These realities likely do not surprise those with a background in American history – that the decisions and policies of the past have an outsized influence on the present. But what may surprise you is that in St. Louis and many other cities, the areas graded “Best” on these maps are often zoned almost exclusively for single-family dwellings. In St. Louis, of the areas graded “Best” in the 1930s, 75% of land is currently zoned exclusively single-family. For the “Still Desirable” category, 50% of land is currently zoned exclusively single-family. Conversely, 21% of Grade C, or “Definitely Declining” areas, is zoned single-family and only 3% of Grade D, or “Hazardous,” is zoned single-family.

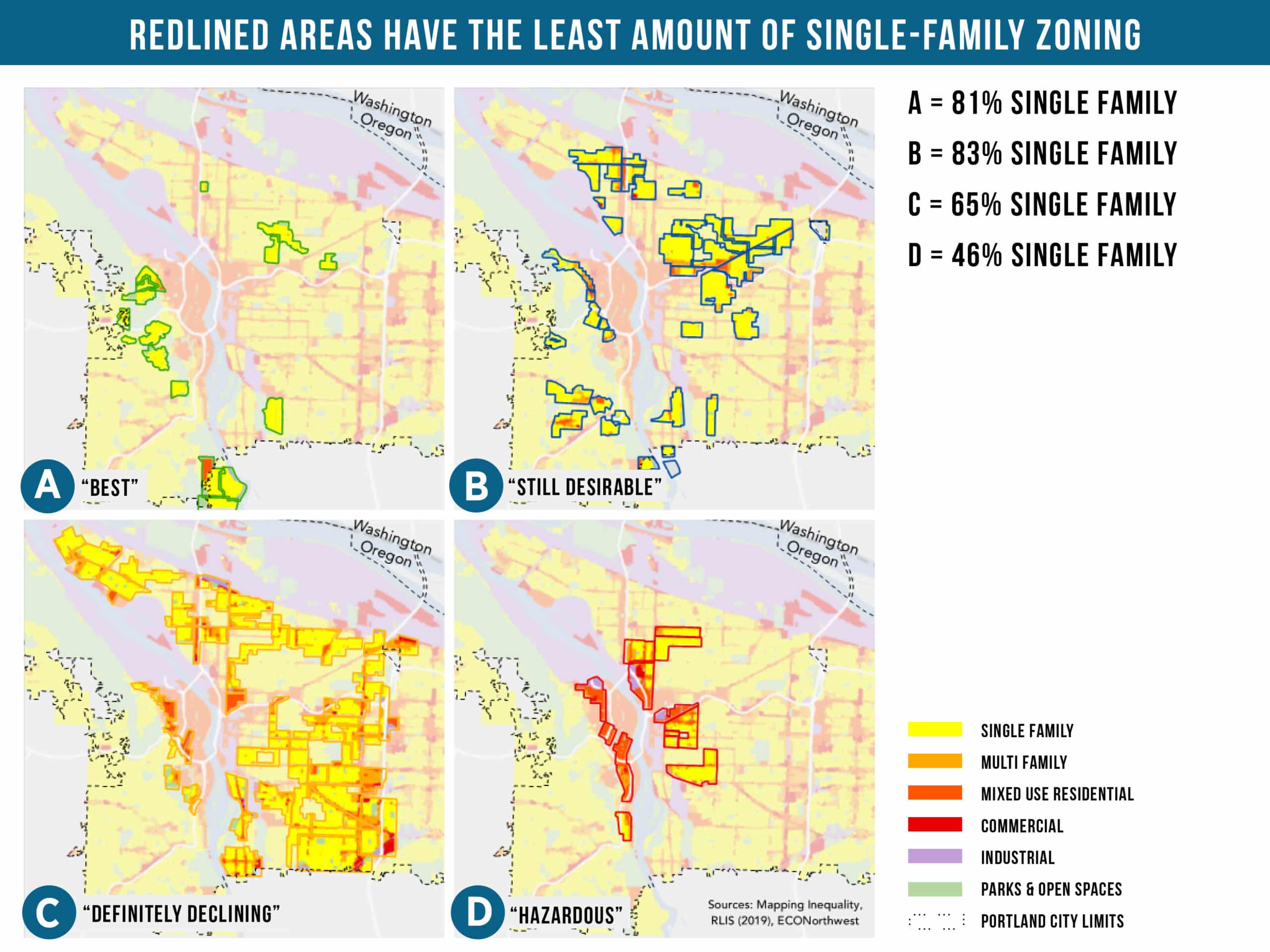

It’s not just St. Louis or midwestern cities that experience this phenomenon. In Portland, Oregon – which on paper does not have much in common with St. Louis other than being cities built along iconic American rivers – similar redlining patterns take shape. 81% of the land in the “Best” category and 83% of the land in the “Still Desirable” category in Portland is zoned exclusively single-family. And the parts zoned as “Hazardous”? Single-family zoning accounts for only 46% of the area in these parts of the city.

Even today, the historic legacy of the places we live affect upward mobility and economic opportunity. The parts of these cities labeled as “Hazardous” or “Definitely Declining” have lower rates of economic mobility than those labeled as “Best” or “Still Desirable.” This tracks with research done by our partners at Harvard University’s Opportunity Insights, which Sebi Devlin-Foltz shared at our recent DC Policy Summit. Children who grow up in areas with high rates of upward mobility earn more as adults, are more likely to go to college, and are generally healthier. His research indicates that incentivizing more housing, and a more diverse array of housing options, in high-opportunity areas – the areas with better outcomes in key indicators – will generate positive impacts for both individuals and society writ large.

What does the legacy of redlining mean in the context of today’s housing shortage and affordability crisis? The fight against denser development in “Desirable” neighborhoods is often taking place in the areas zoned as “Best”, where residents who reflexively oppose new development are unwittingly taking part in a long and ugly tradition of keeping “others” out. Though their motives may be different from the genesis of redlining maps in the Depression era, the outcome is similar.

To solve this 21st Century challenge with roots that go back decades, we need to reduce barriers to building needed housing – both for-sale and for-rent, at all income levels, and in the most job, infrastructure, and asset rich-areas. And we need to do this in the areas that offer the most opportunity to build new housing for all people. Communities have a tremendous opportunity to fight a root cause of inequality by tackling exclusionary single-family zoning and ensuring that a wider variety of for-sale and for-rent housing types are added to existing, high opportunity, single family neighborhoods.