Reading time: 8 minutes

The bottom-line number touted on the City of Portland’s website – 3,913 units created under the new policy – may seem substantial in a vacuum. However, the city’s approach to “measurement” is fundamentally flawed and misleading.

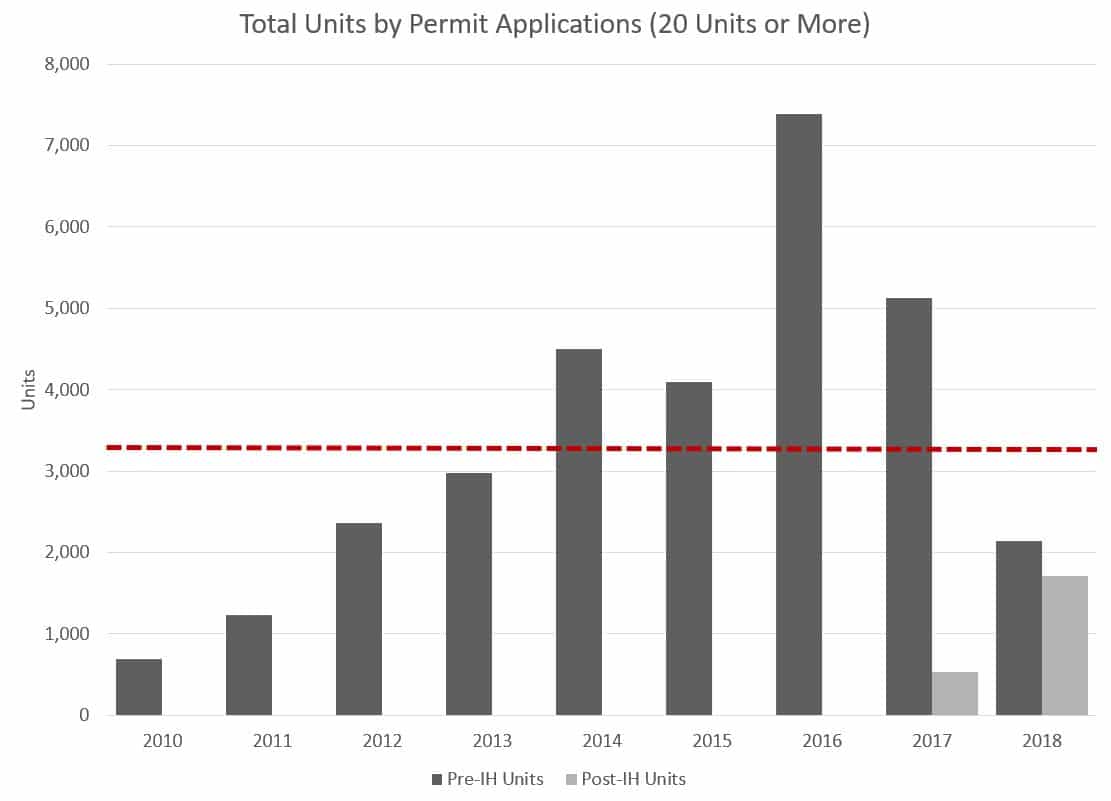

Here’s why the city’s numbers don’t tell the full story. From 2012 – 2017, the City of Portland reports that it issued 3,915 new permits for multifamily units per year. However, as our recent Housing Underproduction in Oregon report discussed, even this level of activity was not enough to keep up with Portland’s rapid population growth and associated housing needs. As the chart below illustrates, in 2018 – the first full year that inclusionary housing was in effect, only 1,709 permits for multifamily units were issued under the city’s inclusionary housing program.

Annual production under the City of Portland’s Inclusionary Housing program represents a 64% decrease relative to the average annual production as measured from 2012 – 2017.

In fact, based on data Up for Growth National Coalition obtained from the City of Portland, the total number of permits issued under Portland’s inclusionary housing program – from February 2017 through March 2019 (a 25 month period) – totaled 2,977 multifamily units. That means that on average, annual post-inclusionary housing permit activity represents 1,429 units per year. Put another way, annual permit issuance under the City of Portland’s inclusionary housing program represents a 64% decrease relative to the 5-year average permit issuance level prior to adoption of inclusionary housing, as measured from 2012 – 2017. Housing starts lag building permit activity, so unless Portland’s inclusionary housing program is significantly restructured soon, we expect this trend line will lead directly to a further underproduction of housing in 2020, 2021 and 2022.

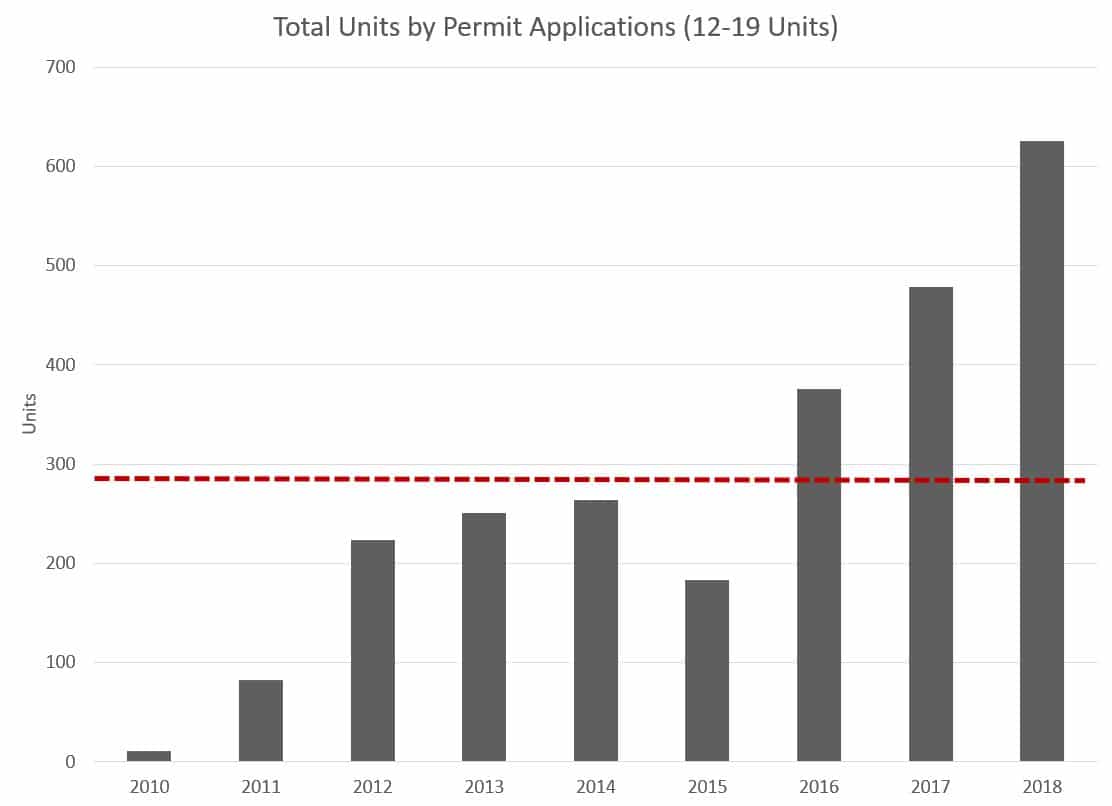

What’s more, the number of projects not subject to inclusionary housing – those under 20 units – are on the rise. Rather than increasing the number of affordable units, the policy appears to be diminishing the supply of housing at nearly all income levels.

Digging deeper, the numbers paint an even bleaker picture. Most of Portland’s recent growth has been amid its livable urban core (thanks to Portland’s history of smart growth land use policies). But today, of the 54 projects submitted to permitting over the past 24 months (i.e. post-inclusionary housing adoption), only two are located in the Central City Plan District, or urban core. This means new projects are being pushed further and further away from downtown, where lower inclusion requirements may make projects more feasible. Away from jobs and amenities, resulting in longer commutes. Away from transit options, meaning more traffic congestion and emissions. Away from the livable and walkable neighborhoods that the city has prioritized, meaning an exacerbation of social inequities. This isn’t some nebulous goal; the city’s 2035 Comprehensive Plan specifically calls for developing the urban core – central to progressive planning goals. This also runs counter to the goals of the City of Portland’s Climate Action Plan.

The data confirms what many experts feared would occur when the city turned to its poorly structured inclusionary housing policy as a response to a very real crisis. Indeed, rents rising by 15% per year should be a call to action for policymakers at all levels. We can all agree such a trend was unsustainable.

The inclusionary housing policy as implemented does two things. It prevents new projects from ever entering the permitting phase because those building the housing can’t make the projects pencil out under the new requirements. And it raises the cost of housing for middle income families who are not eligible for the few units available (i.e. the persons occupying the 80% of the unsubsidized units in each property delivered under the current inclusionary housing program).

These renters are the ones paying for the policy – through ever-increasing rents because supply is not keeping up with demand. In effect, these families are hit with an additional income tax, making it even more difficult for them to reach the American middle-class dream of homeownership and financial security. Notably, this policy has essentially no impact on wealth (i.e. the owners of the properties) – just those renters who occupy the properties.

In reality, Portland’s inclusionary housing policy has forced the city to fall even further behind in meeting its housing needs – both affordable and market rate. A city and region growing as rapidly as Portland can ill-afford to fall even further behind in meeting its housing goals.

Policy based on positive polling but poor economic calibration all too often inflicts harm upon the very persons the politicians claim that they want to help.

From a national perspective, what happened in Portland is a cautionary tale for communities grappling with their own housing shortage and affordability crisis. Housing policy is extremely complicated, and if not done carefully and thoughtfully, can create unintended consequences. Policy based on positive polling but poor economic calibration all too often inflicts harm upon the very persons the politicians claim that they want to help. And despite data that has raised red flags for at least a year, there has been little willingness by the city to consider recalibrating the inclusionary housing policy to keep housing production moving forward.

Both the public and private sectors must work together to ensure housing policies are indeed solving the problem rather than exacerbating it. Both have a role to play and there is no reason these roles need to be adversarial. Our end goal is the same: more housing to accommodate a growing city.

In the final analysis, the City of Portland’s own data contradicts their own recent claims of success. Portland truly is one of the most progressive cities in the country. We know its leaders are genuinely concerned about the high cost of housing and ensuring that their city is equitable for all. But when those policies aren’t achieving the desired goal, and even make the problem worse, the public deserves transparency, truth, and honesty so that we can all be part of fixing it. Unfortunately, Portlanders are getting both bad policy and bad information while the city suffers from the high cost of housing.