Reading time: 6 minutes

Up for Growth Action advocates for more households – of all income levels – to live near high frequency or high-capacity transportation options. We believe this is good for both the families who would live in these homes, the communities that would benefit from less congestion and fewer cars on the road, and the health of our environment. It’s also good for the workers who are currently forced to live farther and farther away from job opportunities.

A major factor limiting transit usage – and thus, public transit’s inherent environmental benefits – is that low-density zoning regulations restrict the number of houses that can be built in transit-served neighborhoods. Allowing more people to live near high-frequency transit and job opportunities, with safe, accessible, and connecting choices for walking, biking, light rail, bus, and the subway, promotes public health and preserves open space, farmlands, and the natural beauty of the surrounding geography.

A state where we have taken a close look at how housing policy impacts the environment is Oregon, which is currently considering a full slate of housing legislation, including allowing more housing in urban growth boundaries and in communities with transit options. Although Oregon is a leader in environmental sustainability practices, most of its housing is produced in ways that do not facilitate sustainable transportation options. Two thirds of the housing in Oregon is low-density single family and only 4% is considered high-density. Limiting housing options close to transit means that people must travel farther for access to jobs, education, and services. Additional time spent traveling means more air pollution and more congestion on both highways and surface streets.

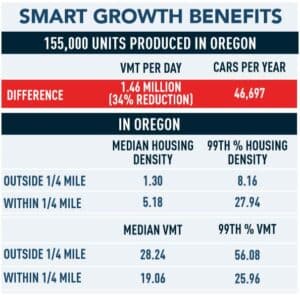

Shifting from current development patterns to denser growth centered around transit would result in 1.5 million fewer vehicle miles traveled daily in Oregon – a 34% reduction and a difference equivalent to 46,700 fewer cars on the road each year. Building housing near quality transit could save Oregonians time, money, and stress. It can also be a meaningful part of Oregon’s path toward cutting carbon emissions and reaching sustainability goals.

Oregon has strong land-use policies governing growth management and protecting forestland and farmland – amenities Oregonians value. However, the state must make the best use of the land inside each growth boundary. According to our Housing Underproduction in Oregon report, building new homes in denser developments centered around high-capacity transit would require 82% less land than building the same number of homes under current low-density development patterns – achieving twin goals of greenfield preservation and removing cars from the roads.

Oregon has strong land-use policies governing growth management and protecting forestland and farmland – amenities Oregonians value. However, the state must make the best use of the land inside each growth boundary. According to our Housing Underproduction in Oregon report, building new homes in denser developments centered around high-capacity transit would require 82% less land than building the same number of homes under current low-density development patterns – achieving twin goals of greenfield preservation and removing cars from the roads.

Housing Underproduction in the U.S. came to similar conclusions for the 22 states and the District of Columbia that were covered in the report. Shifting to a “smart growth” approach that prioritizes density would require only 25% of the land used under current housing construction patterns. Vehicle miles traveled would be reduced by 28%. These benefits are in addition to the primary selling point of changing where and how we build our communities: eliminating our 7.3-million-unit housing shortage and reducing the cost of housing.

Of course, combating climate change necessarily entails reducing our carbon output and carbon footprint. That’s why it makes sense to spend time, precious research dollars, and political capital in an attempt to “green” our transportation fleet. Indeed, proposals like the Green New Deal focus on heavily on reducing carbon from transportation, including a quite ambitious goal of completely electrifying both passenger and commercial vehicles by 2050. But, as Alex Baca noted in an analysis of the Green New Deal, making transportation greener will be limited in its impact unless we address how far we live from public transit and how far we live from work and amenities, all of which have a disproportionate impact on our individual and collective carbon footprints.

Another reason to incorporate housing policy into fighting climate change? Cost. Enabling denser housing near transit and amenities does not require massive public investment. For the most part, it’s simply a matter of a change in public policy to allow more of a public good. Whether in Oregon or across the United States, changing our approach to housing is a transformation we can begin tomorrow if the right policies are put into place.

For additional reading on this topic, Jenny Schuetz of Brookings has a smart, urban land use critique of the Green New Deal.